An interview with a unionist in the ECEC sector

Question: What are the conditions like for early childhood educators in NSW?

Early childhood education, alongside cleaning, aged care, and school support roles, are the lowest paid in the country. Unsurprisingly, they are also amongst the most feminised too.

The majority of early childhood educators across the country are on the children’s services award, which has starting rates at about $23 per hour. Many are on even less as trainees, who are often employed on the (lower) trainee wage for the year while their boss collects funds for ‘educating them’.

Some large providers, like Goodstart, have an enterprise agreement. In NSW if you’re employed by Council, or are at a state-run pre-school, then you’ll generally be under the public sector awards, which are better but still not great when you consider the intensity of the job. It synthesises a lot of the intellectual demands of a school teacher, while requiring a lot of the same physical labour expected of a cleaner.

The very last equal pay orders in our country, which allowed women teaching in schools to be paid the same as men, never applied to educators in the early years. Arguably, we are still on that female wage, and I would argue that most jobs in Australia, with over 80% women, are in the same position as they are not considered ‘real’ work.

Most educators (74% based on an UWU survey) are planning on leaving the sector soon, because the pay is too low to deal with cost of living and there is too much paperwork to keep up with. Not to mention the physical labour, the constant infections (have fun regularly getting gastro for the rest of your life) and the risk of eventually injuring your back. This results in a burn out rate of 1 – 2 years, and an industry that is in crisis.

Another factor is disrespect. Educators know that we’re not valued, despite the way we were called essential during covid lockdowns. It creates an ongoing demoralisation. At the council centre that I work for, people have referred to themselves [educators] as ‘the scum, the lowest of the low’ of the organisation.

This comes after we have done unpaid placements for our course work in order to start working. The salary sacrifice of these hours over the length of qualifications can be worth over $10k. It’s a huge obstacle where our sense of self-respect is ground down until we leave.

To put it all bluntly, we set up and pack up equipment, we handle shit and urine constantly, we clean up, we serve food, we do lesson plans, constant paperwork, get sick all the time, and then we get paid fuck all and looked down upon for having done this ‘essential job’. It’s a joke.

Everyone has been expecting us educators to suck it up and keep subsidising this collapsing industry. Every boss and level of government pays lip service to the reality that we need a pay rise, but then passes the buck to someone else in the chain to delay action.

Cruelly, the government is trying to delay dealing with that by making this a priority area for migrant workers. It is not plugging the gap and the industry is continuing to implode, but it is sending a layer of immigrant women into continuing poverty as they search for oppressed people to underpay and overwork.

To put it all bluntly, we set up and pack up equipment, we handle shit and urine constantly, we clean up, we serve food, we do lesson plans, constant paperwork, get sick all the time, and then we get paid fuck all and looked down upon for having done this ‘essential job’. It’s a joke.

Everyone has been expecting us educators to suck it up and keep subsidising this collapsing industry.

Question: Is there any difference in the conditions between the private and public sectors of the industry?

The public sector in NSW is broken up into 260 or so council-run centres, 100+ state run pre-schools, and then maybe 20 which are run variously by universities, hospitals, and TAFE. This amounts to about 10% of the ECEC sector in NSW, and being covered under different awards they all generally pay better than private centres.

The private sector has a few major providers, including not-for-profits like Goodstart, and they will sometimes have enterprise agreements which pay above the children’s services award. And then there is a very very large number of small business owners, some of whom run family day care out of their own homes.

There’s no other way to describe the children’s services award – which covers most private centres – than utter rubbish. I do not believe it is possible for a centre to legitimately meet the National Quality Standards if they are paying their staff on the children’s services award. Unfortunately that is the majority of the sector in NSW.

This needs to change – publicly run ECEC needs to be the norm so we don’t have small businesses who keep educator wages even lower so that these small businesses can pay the rent and rake in fees from families in the northern suburbs.

I’m covered by a public sector award, which is outdated and we are bargaining for better, but we do get things like a waste allowance for having to handle faeces. This is an important win. Our pay conditions are also better to start with as we are well unionised and part of the same actions as other public sector employees.

But our pay is also falling behind and is not rising to meet Sydney’s rent and mortgage increases. We do not have the sick leave to keep up with constant covid, gastro, flu, rsv. And we are still burning out under the heavy workloads.

Question: What are the workers demanding for this agreement?

The private sector educators, who are covered by the United Workers Union, are campaigning for what is called a multi-enterprise agreement whereby a range of capitalists across a sector bargain together with the union. Theoretically this means unionists are legally able to strike in solidarity with each other across these sites, under the new laws.

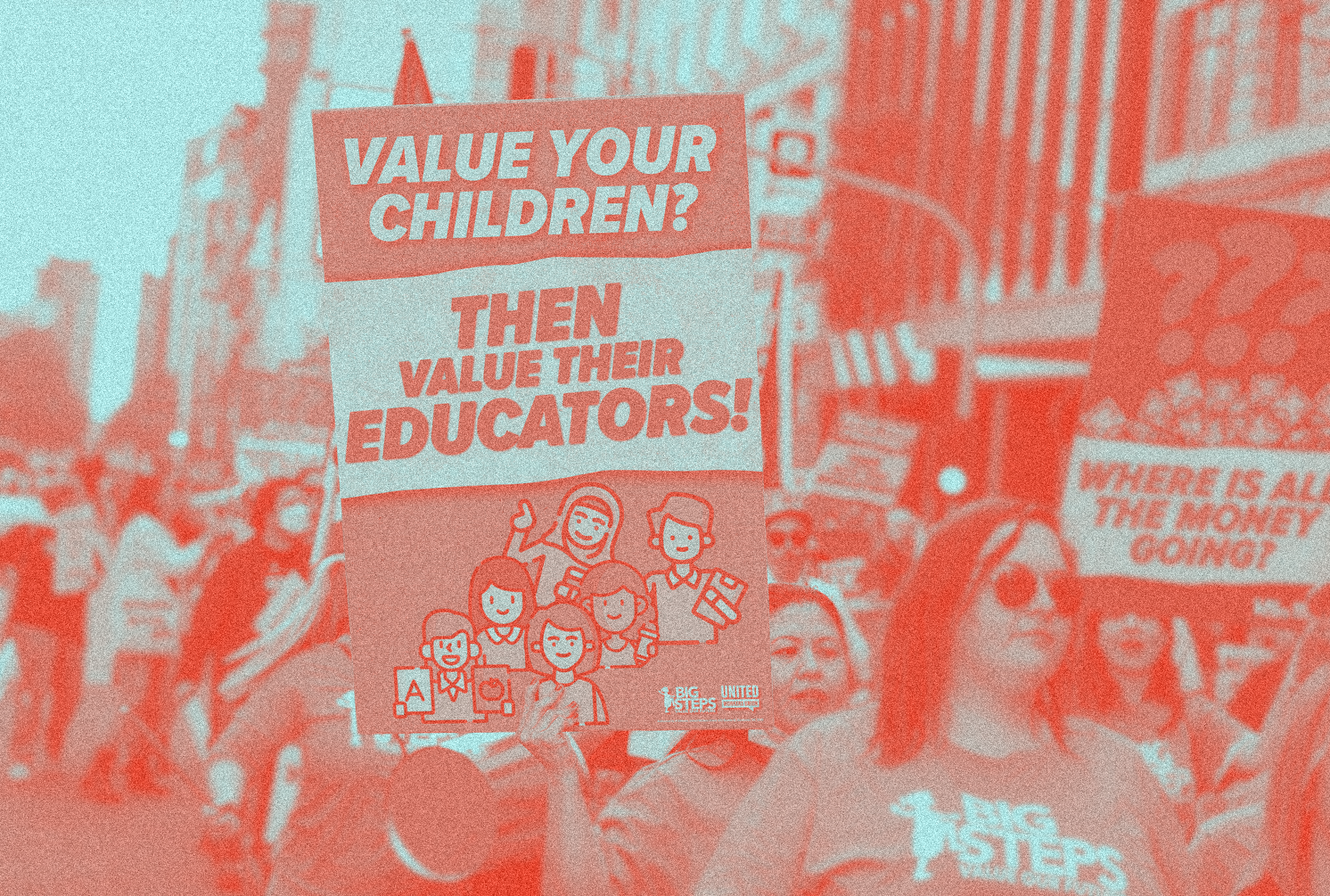

The UWU is bargaining with one of the major providers, G8, and a large number of parent run co-op providers via the Childcare Alliance. The most prominent demand of their campaign, Big Steps, is for a 25% pay increase and the union leadership has formed a popular front with business and called upon the Labor government to fund the providers to pay the wage increase for their staff. The capitalists have more or less signed off on the union’s demands if the Labor government will come to the table with funds.

We shouldn’t be uncritical of Big Steps. The popular front strategy and funding for the private sector is far from ideal – as is the fact that the majority of private sector union delegates are actually the directors of their centre – but this is an improvement on where the Big Steps campaign was beforehand. Their multi-year pay case before the Fair Work Commission had failed, as had their investment in the 2016 and 2019 Labor elections.

The public sector union campaign for council centres, run through the United Services Union, is a bit different. We are covered under the Industrial Relations Commission, rather than Fair Work, and the local government award. We are seeking a splinter award to sit alongside the broader award so as to add specific details about our wages and conditions.

We will be re-visiting the log of claims in February as Local Government NSW (the bargaining rep for the bosses) has committed to bargain at its last conference. Following a successful motion by Greens councillors for a pay rise above inflation, paid placements, adequate sick leave, and more the management team are required to make an offer to us along those lines.

The union membership has to then make its counter-offer to management which will be voted on in late February or early March. My suspicion however is that the Minns Labor minority government will need to come to the table as well, as they control council’s revenue.

We can and should be outlining a vision of fee-free and public early childhood education and care in every suburb, with well paid educators, and ultimately an end to gender segregation and inequality. We know this can only be achieved by class struggle, so let’s commit to being there every step of the way.

Educators in the private sector are doing stop-work actions around the country for equal pay on International Working Women’s Day. In Sydney, they will be meeting at 3 pm, Martin Place.

This also lands on the ‘union picnic day’ for the public sector union, which entitles union members to a day off. It is my hope that we can join our private sector comrades in solidarity on the day.

It is politically quite significant that this action is happening in IWWD because the issue of ECEC pay and conditions isn’t a simple question of how well a section of workers are paid. It’s also inviting everyone to ask why we are paid so poorly, and the fundamental answer to that is: sexism. And the only way to fight sexism is through class struggle.

Historically, labourism in the Australian colonies often tried to take the shortcut of keeping women and immigrants out of the workforce in order to keep wages for white men high. It leaned into bigotry when it should not have, and supported wage inequality for women workers for a very long time. This gradually changed on the legal level after equal pay campaigns, but the gender segregation of our labour force allows much of it to persist.

The very last equal pay orders in our country, which allowed women teaching in schools to be paid the same as men, never applied to educators in the early years. Arguably, we are still on that female wage, and I would argue that most jobs in Australia, with over 80% women, are in the same position as they are not considered ‘real’ work.

But it being on IWWD doesn’t just invite us to consider the pay gap issue, but how service provision is part of gender inequality. The suburbs with the most domestic violence are those with a scarcity of services that enable women’s economic independence—it’s not just a lack of shelters and welfare but a lack of early learning centres and well-paid jobs with solid parental leave.

If centres chase profits from wealthy families in the northern suburbs, then we are also creating spaces where women in straight relationships are financially dependent on their husbands if they have children but no centre to enrol them.

It’s also not just added political context for a stop-work action, but a welcome corrective to girl boss corporate breakfasts or rallies run by SWERF/TERF losers.

This is what we should be thinking about as we stop work this IWWD. This fight is not just about a work site, but about how this world is run and for whom.

[NOTE: Since this interview was conducted, IWWD has passed and the planned ECEC strike mentioned above was shamefully called off by ALP-aligned union officials. This was ostensibly in response to recent shifts in bargaining, however it is clear that there was also a desire to not ‘hurt’ the ALP’s image on International Women’s Day. Though frustrating for the members who built this action for weeks, this does serve as a further reminder of the importance of an independently organised and politically coherent network of rank-and-file members, willing to challenge the union bureaucracy.]

Question: How can we build solidarity among other existing industrial and feminist campaigns in particular?

The frank reality we need to accept is that both liberal feminism and radical feminism not only have dominated discourse, but that union militants have accepted this and historically argued to the right of feminism. A prominent example being the Communist Party’s historical position on abortion as ‘bourgeois’.

This isn’t due to the left being inherently sexist compared to the rest of society, or other liberal gotchas. But we have mostly given up on outlining an alternative vision to fighting systemic sexism, which leaves people in the position of either tailing libfems and radfems, or providing only theoretical responses to these approaches.

Moments like these can provide openings to change that. We can and should be outlining a vision of fee-free and public early childhood education and care in every suburb, with well paid educators, and ultimately an end to gender segregation and inequality. We know this can only be achieved by class struggle, so let’s commit to being there every step of the way.

Parents, in particular, have a sizable role to play in this campaign, and that includes industrial action. The self-organisation of parents – whose children will benefit from wins – can reduce the viability of centres paying agencies for scab labour by keeping children at home.

There is nothing stopping families, or anyone who plans on children, from calling their own community meetings about changing this system, initiating parent letters calling for action, and more. If you think these issues are important, then I encourage you to call a meeting and plaster the neighbourhood in posters.

You also do not need to wait for our union to take the lead on every aspect. If you are a student, then there’s nothing stopping you from campaigning for your university to run in-house free early childhood education and care covered by the NTEU agreement, and this is timely given attempts by university bosses to outsource services at most campuses. Similarly most large hospitals used to run in-house ECEC, and it can be that way again.

These kinds of struggles naturally lead to building solidarity contingents to each other’s actions.

There are also other fights in the sphere of workers’ rights that also directly raise the questions of the role of women in society. The fight to decriminalise and destigmatise sex work and unionise sex workers is a just cause that we should all be willing and ready to support with the upcoming Equality Bill.