Labour Day is a strange public holiday: like the King or Queen’s Birthday, it comes and goes without much fanfare. People either enjoy the day off or enjoy the public holiday pay. Even for those on the left or in the labour movement, it tends to be a minor event, dwarfed by the main draw on the 1st of May.

A little bit of history

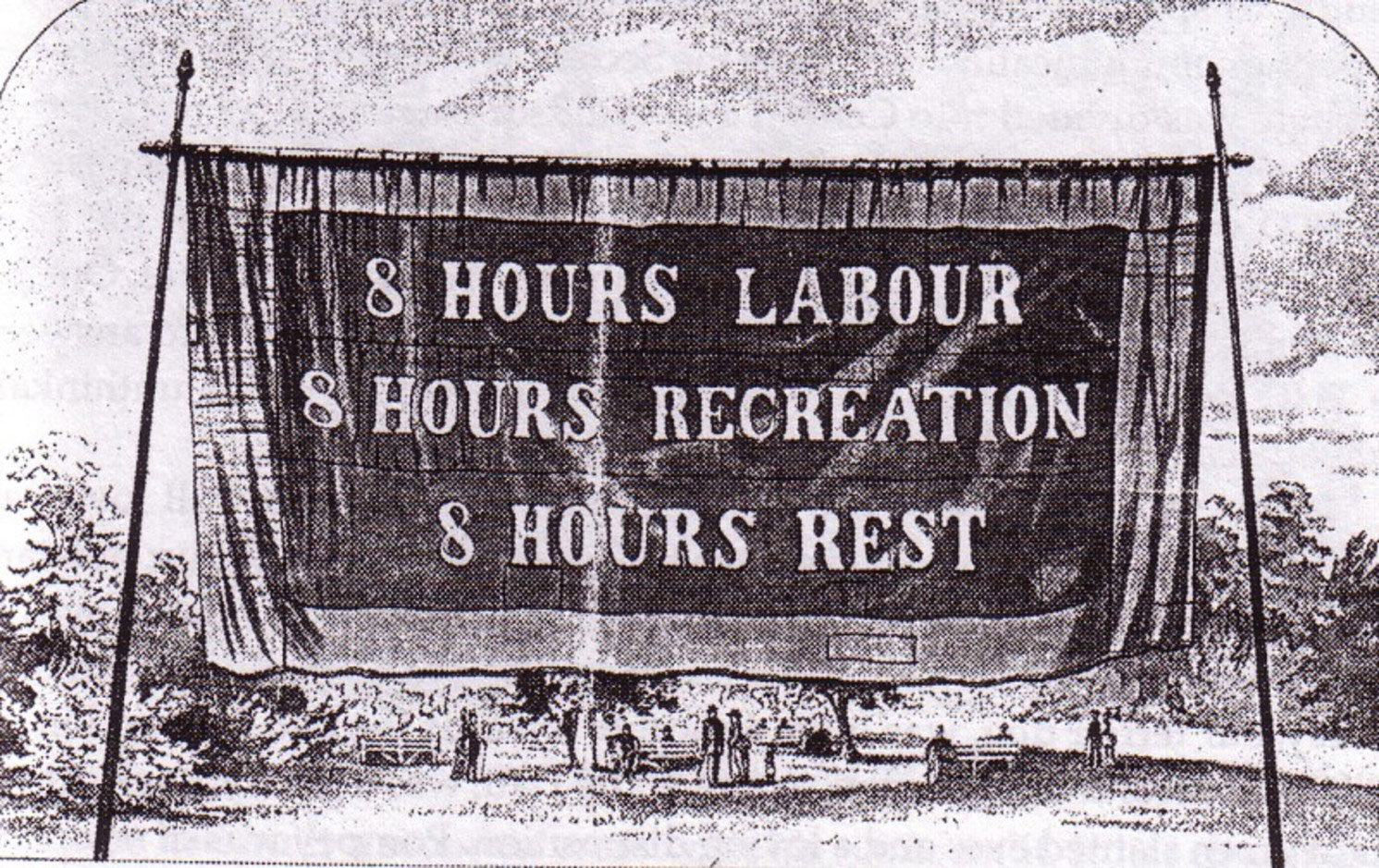

The history of Labour Day goes back to the mid-1800s and is tied up with the development of the campaign for the eight hour day – so much so, that the day itself used to be known as “Eight Hours Day”. This was a period where skilled workers would, on average, work ten hours every weekday, and eight on Saturdays. For unskilled workers, the hours were even longer, and the work more onerous.

Nor were children exempt from this nightmare. In 1884, a witness speaking before a Royal Commission in Victoria reported on the working conditions of newspaper printers:

Boys of the most tender years are employed at excessive and unreasonable hours […] and they are compelled to work every night in the week […] from three or four in the afternoon till about three the following morning […] in a room filled with impure air and lighted gas.

It’s no surprise then that the “eight hour” movement spread like wildfire and became one of the first industrial campaigns to cross boundaries of trade and industry, a real demand of the whole working class.

One of the first decisive blows was struck in Sydney by organised stonemasons. At the time masons would generally work a twelve hour day, starting work at six in the morning and finishing at six in the evening. Thanks to their skilled trade, they were not easily replaceable. This fact granted them a degree of leverage that went beyond their rather small numbers – in 1885, there were approximately three hundred stonemasons working in Sydney, with around half belonging to the newly formed Operative Stonemasons’ Society.

On the 18th of August that year, the Society met and agreed on an ultimatum to employers – that in six months time, stonemasons would not work more than eight hours a day. By the time February rolled around, the employers had not shifted, so the organised masons struck. For two weeks they held out against the resistance of the employers until victory was secured.

But why then is Labour Day celebrated in early October, not August or late February? In the days after the ultimatum was first delivered, enthusiastic masons on two separate sites in the city decided not to wait, and immediately struck for the eight hour day. Beyond expectations, they won, and celebrated their victory with a dinner on the 1st of October. That date would become the traditional day of celebration for workers in New South Wales.

The message of the day

A lot can be learned by comparing the victory of the stonemasons to present day industrial disputes. Contemporary industrial disputes are complicated affairs, usually stage-managed by union bureaucrats who find it easier to deal with the various government commissions and “independent” arbitrators than with rebellious workers. The disputes are governed by a byzantine IR law system which saddles any action with onerous legal requirements, to the obvious disadvantage of workers. The average worker in the middle of an EBA dispute feels less like a protagonist and more like a bit player in a wider dispute they have little control over.

The stonemasons’ battle, on the other hand, was simple and elegant: a meeting of unionists agreed to set a clear demand and strike if it was not met. When it was not met, they struck until they won. They utilised their chokehold over a section of the production process to strangle their employers. A minority of them jumped the gun and struck of their own accord again until they won. They didn’t win by lobbying crossbench MPs, making submissions to an IR court, or conducting a media campaign through sympathetic journalists. The campaign revolved around workers on strike, not a boardroom meeting between union staffers and corporate suits.

For us, the stonemasons have given us an important lesson: that direct action wins! Émile Pouget captured what this meant very well:

It means that the working class, in constant rebellion against the existing state of affairs, expects nothing from outside people, powers or forces, but rather creates its own conditions of struggle and looks to itself for its means of action. It means that, against the existing society which recognises only the citizen, rises the producer.

This is one of the reasons why we advocate for workers to use their social power to challenge the IR system head-on, and to see the Labor Party as an enemy, not a friend. The stonemasons achieved their victory in a period before the monstrous system of industrial law properly developed. It was also a period in which the institutions and the leadership of the working class had not yet been integrated into the bourgeois state, thanks to the successes of the ALP.

While Labor leaders, union officials and government figures may celebrate Labour Day as a holiday for their own tradition, we choose to celebrate it as a holiday for working class militancy, in the name of shorter hours and higher wages. In a period where around 38% of Australians still work more than forty hours a week, it would be class treason not to.