On the 9th of November 2019, Kumanjayi Walker was shot and killed by Zachary Rolfe in the remote community of Yuendumu, some 300km from Alice Springs. In the hours leading up to his death, 4 heavily armed police officers had been deployed to find and arrest Kumanjayi Walker. Upon his finding, officers Rolfe and Eberl brutalised Walker, punching him in the head and face, before Rolfe shot him three times in the back and torso. Walker was then taken to Yuendumu police station, where he was later pronounced dead.

Kumanjayi’s murder is not an isolated instance of police brutality against First Nations people in this country. As of the writing of this article, he is one of 517 Aborginal people who have died in custody since the Royal Commission into Black Deaths in Custody in 1991.

In the aftermath of Kumanjayi Walker’s murder, Zachary Rolfe was arrested and charged with murder. This followed a wave of protests across the country, and was announced while a large segment of the Yuendumu community were en route to protest in Alice Springs. By 2022, Rolfe was on trial for murder, an unprecedented event spurred on by both the horrific brutality revealed by the investigation, but also as a reaction to mounting pressure from the First Nations community to see justice in response to police brutality, in part inspired by the events following George Floyd’s murder in America. The ensuing trial ultimately found Rolfe not guilty of murder, and today he is a free man.

Now, a coronial inquest has begun to probe the events surrounding Walker’s death, as grieving community and family members seek to find truth and action in the hope that his death is not in vain. Coronial inquests have historically been ineffectual, with findings and subsequent recommendations never seeing the light of day, and often even working to actively protect prison guards and police officers by clearing them of any wrongdoing – as in the case of David Dungay’s murder in 2015.

The picture painted by the Kumanjayi Walker murder, among the many hundreds of instances of police brutality against First Nations people is clear: Aboriginal people are systemically targeted and subject to abuse, humiliation and murder by racist police, judicial and carceral systems.

In response, the government has offered a number of ineffective legislative proposals over the years. Most recently, and carrying the most momentum is the Uluru Statement, which through the parliamentary process of reform has transformed away from demands of Truth and Treaty and towards installing a Constitutional Indigenous Voice to Parliament. A compromised deal with the right of parliament and business sector, the Voice to Parliament has been whittled down to a meek advisory role, holding no binding power to impact legislation and reform, and garnering heavy criticism from the grassroots First Nations community. Such approaches from the government are watered down by design: they exist only to produce a thin veneer of justice and social progress, intentionally overlooking the necessity of pulling apart racist and oppressive systems and rebuilding them.

Legislation projects such as the Uluru Statement and the Royal Commission into Black Deaths in Custody all point in the same direction; they serve only as the parliamentary strategy to quiet outrage, and to maintain status quo. They uphold racist institutions which cast First Nations people as ‘defective’ and ‘broken’. Only through a ‘bottom-up’ approach of collective struggle can the First Nations’ communities see any tangible justice, and the details of the campaigns from grassroots and First Nations’ communities reveal this contrast most pointedly.

In May of this year, the Yuendumu community released a statement of demands outlining a comprehensive programme that would meaningfully transform society and impact the material conditions of community members who are subject to the effects of systemic racism and colonisation.

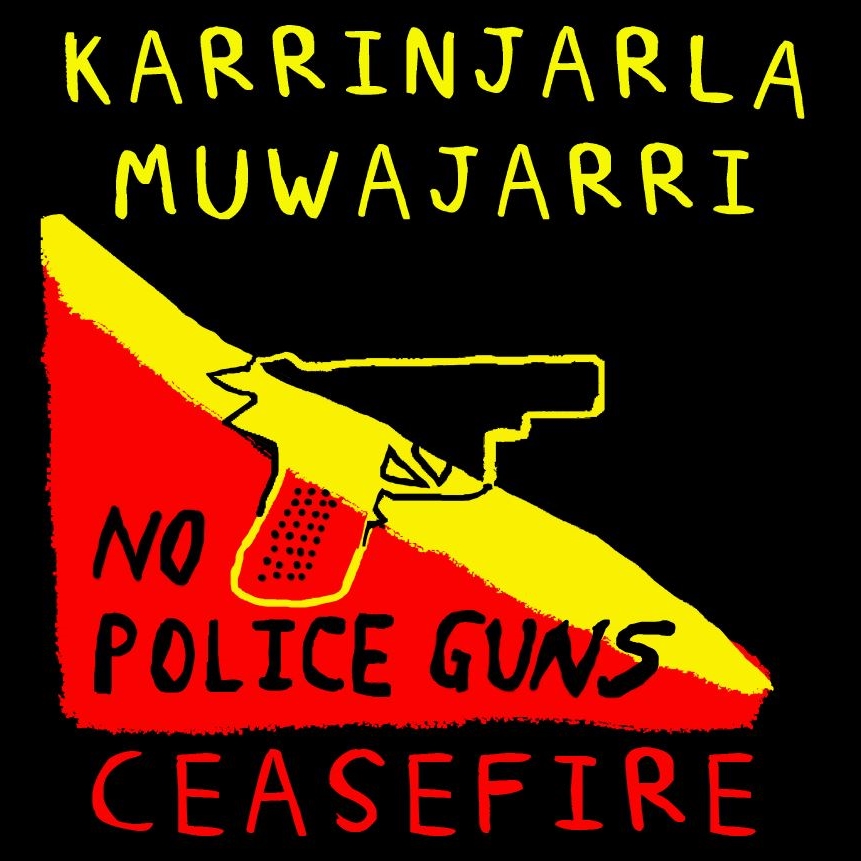

In this statement, the Yuendumu community demands key strategic reforms, including autonomy away from oppressive colonial policing and toward community based approaches, an end to the racist Northern Territory Intervention laws, increased funding in community sectors such as housing, employment and health, accountability of the press which published lies about the nature of Walker’s murder and finally, a comprehensive overhaul of the justice and courts system, and a retrial of Zachary Rolfe.

These demands mirror many of the programs around the country and the world calling for an uprooting of the racist systems that continue to oppress marginalised groups. The Deaths In Custody Project and ongoing protest movement similarly demands that the findings and 330+ recommendations of the Royal Commission of 1991 be implemented. They call for the defunding of police, with the money instead used for community programs and initiatives.

It is only through the realisation of these transformative programs that the cycle of abuse handed down from the state and its judicial, carceral and police arms can be put to an end. It is our duty therefore to stand in solidarity with working-class First Nations communities, and to ensure we bring the Yuendumu demands to every workplace and grassroots organisation in which we participate.

These demands are specific, clear, and focused on real, material change. They have been formulated by the community themselves, not political representatives and popular figures. These should be the focus of our campaigns for Indigenous justice, not symbolic changes like ‘constitutional recognition’, and we hope that other communities take inspiration from Yuendumu to form their own self-determined vision for material reform.